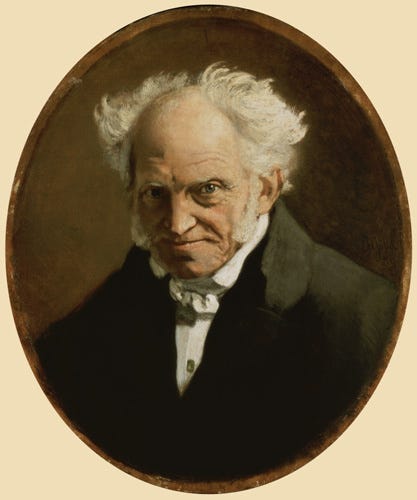

Would Schopenhauer Allow Comments?

If Schopenhauer had been a blogger, would he have allowed comments on his weblog, The Scowl of Minerva?

I say no, and adduce as evidence the following passage that concludes his Art of Controversy, a delightful essay found in his Nachlass, but left untitled by the master. It is followed by the same passage in the German original.

As a sharpening of wits, controversy is often, indeed, of mutual advantage, in order to correct one's thoughts and awaken new views. But in learning and in mental power both disputants must be tolerably equal: If one of them lacks learning, he will fail to understand the other, as he is not on the same level with his antagonist. If he lacks mental power, he will be embittered, and led into dishonest tricks, and end by being rude.

The only safe rule, therefore, is that which Aristotle mentions in the last chapter of his Topica: not to dispute with the first person you meet, but only with those of your acquaintance of whom you know that they possess sufficient intelligence and self-respect not to advance absurdities; to appeal to reason and not to authority, and to listen to reason and yield to it; and, finally, to cherish truth, to be willing to accept reason even from an opponent, and to be just enough to bear being proved to be in the wrong, should truth lie with him. From this it follows that scarcely one man in a hundred is worth your disputing with him. You may let the remainder say what they please, for every one is at liberty to be a fool - desipere est jus gentium. Remember what Voltaire says: La paix vaut encore mieux que la verite. Remember also an Arabian proverb which tells us that on the tree of silence there hangs its fruit, which is peace.

Das Disputieren ist als Reibung der Köpfe allerdings oft von gegenseitigem Nutzen, zur Berichtigung der eignen Gedanken und auch zur Erzeugung neuer Ansichten. Allein beide Disputanten müssen an Gelehrsamkeit und an Geist ziemlich gleichstehn. Fehlt es Einem an der ersten, so versteht er nicht Alles, ist nicht au niveau. Fehlt es ihm am zweiten, so wird die dadurch herbeigeführte Erbitterung ihn zu Unredlichkeiten und Kniffen [oder] zu Grobheit verleiten.

Die einzig sichere Gegenregel ist daher die, welche schon Aristoteles im letzten Kapitel der Topica gibt: Nicht mit dem Ersten dem Besten zu disputieren; sondern allein mit solchen, die man kennt, und von denen man weiß, daß sie Verstand genug haben, nicht gar zu Absurdes vorzubringen und dadurch beschämt werden zu müssen; und um mit Gründen zu disputieren und nicht mit Machtsprüchen, und um auf Gründe zu hören und darauf einzugehn; und endlich, daß sie die Wahrheit schätzen, gute Gründe gern hören, auch aus dem Munde des Gegners, und Billigkeit genug haben, um es ertragen zu können, Unrecht zu behalten, wenn die Wahrheit auf der andern Seite liegt. Daraus folgt, daß unter Hundert kaum Einer ist, der wert ist, daß man mit ihm disputiert. Die Übrigen lasse man reden, was sie wollen, denn desipere est juris gentium, und man bedenke, was Voltaire sagt: La paix vaut encore mieux que la vérité; und ein arabischer Spruch ist: »Am Baume des Schweigens hängt seine Frucht der Friede.«