George W. Bush once referred to Jesus Christ as his favorite political philosopher, thereby betraying both a failure to grasp what a philosopher is and who Jesus claimed to be.

Jesus Christ is not a philosopher. The philosopher is a mere lover of wisdom. His love is desirous and needy; it is eros, the love of one who lacks for that which he lacks. But Jesus Christ lacks nothing; he is the fullness of wisdom, the Word and Wisdom of God embodied. So Christ is no lover of wisdom in the strict sense in which Socrates is a lover of wisdom. Divine love is not erotic but agapic.

If a sage is a possessor of wisdom, no philosopher qua philosopher is a sage. If a philosopher were to become a sage, he would thereby cease to be a philosopher: one does not seek what one possesses. Socrates is the embodiment of philosophy but not of wisdom. Socrates, then, is not a sage. Wise, but not a sage.

The wisdom of Socrates was largely the wisdom of nescience: he knew that he did not know what he did not know. In stark contrast, Christ claimed not only to know the truth, but to be the truth as recounted in the via, veritas, vita passage at John 14:6: "I am the way, the truth, and the life; no one comes to the Father except through me." Ego sum via et veritas et vita; nemo venit ad Patrem nisi per me.

Suppose a philosopher comes to accept Christian doctrine. Does he remain a philosopher in his acceptance of Christian doctrine or does he move beyond philosophy? I say that a philosopher who accepts the revealed truths characteristic of Christianity has moved beyond philosophy in this acceptance. Why?

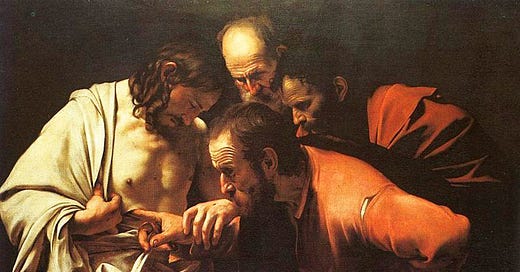

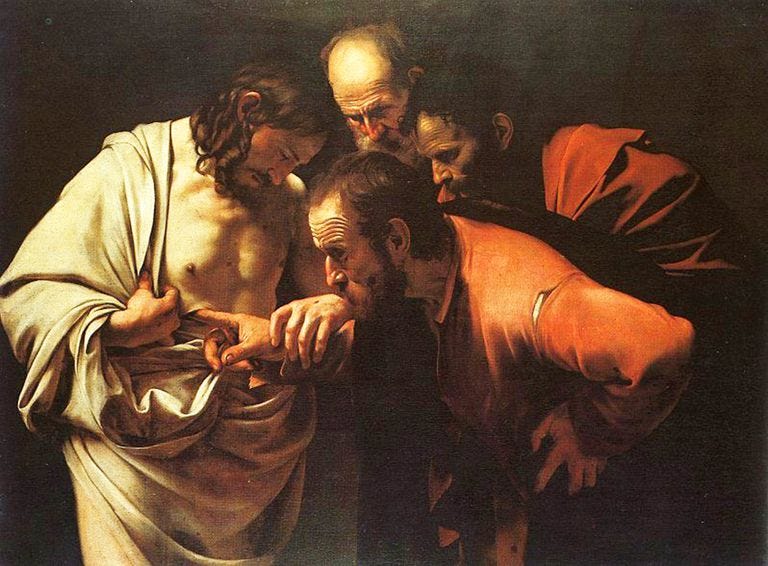

A philosopher is not only one who, lacking wisdom and desiring it, seeks it, but also one who seeks the truth in a certain way, by a certain method. It is characteristic of philosophy that it is the pursuit of truth by unaided reason. 'Unaided' means: not aided by divine revelation. (It does not mean that the philosopher does not consult the senses.) The philosopher operates by reason and seeks reasons for what he believes. The philosopher relies on reason as he encounters it in himself and accepts only what he can validate by his autonomous use of reason. Qua philosopher, he accepts no testimony but must verify matters for himself. The philosopher is like Doubting Thomas Didymus at John 20:25: "Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails and put my finger into the place of the nails and put my hand into his side, I will not believe."

That is the attitude of the philosopher. The philosopher is an inquirer into ultimate matters, and doubt is the engine of inquiry. The philosopher qua philosopher asks: Where's the evidence? What's the argument? What you say may be true, my brothers, but how do you know? What's your justification?

You say our rabbi rose from the dead? That sort of thing doesn't happen! I want knowledge, which is not just true belief but justified true belief. You expect me to believe that Jesus rose on no evidence but your testimony from probably hallucinatory experiences fueled by your fear and hunger and weakness? Prove it! W. K. Clifford takes it to the limit and gives it a moral twist: "It is wrong always and everywhere to believe anything on insufficient evidence." Presumably the testimony of a bunch of scared, unlettered, credulous fishermen would not count as sufficient evidence for Thomas Didymus or Clifford.

The Christian, however, operates by faith. If Reason is the faculty of philosophy, Faith is the faculty of religion. The philosopher may reason his way to the existence of God and the immortality of the soul, but he cannot qua philosopher arrive at the saving truth that "the Word became flesh and dwelt among us" (John 1:14) by the use of reason. The saving truths are 'known' by faith and not by reason. It is also clear that faith for the Christian ranks higher than reason. As Jesus says to Thomas at John 20:29: "Because thou hast seen me, Thomas, thou hast believed: blessed are they that have not seen and have believed."

The attitude of the believer who is also a philosopher is fides quarens intellectum, faith seeking understanding. But what if no understanding is found? Does the believer reject or suspend his belief? Neither. If he is a genuine believer, he continues to believe whether or not he achieves understanding. This shows that for the believer, reason has no veto power. The apparent logical impossibility of the Incarnation does not cause him to reject or suspend his belief in Jesus as his Lord and Savior. If he finds a way to show the rational acceptability of the Incarnation, well and good; if he fails, no matter. The Incarnation is a fact 'known' by Revelation; as an actual fact it is possible, and what is possible is possible whether or not we frail reeds can understand how it is possible. The believer in the end will announce that the saving truths are mysteries impenetrable to us here below even if he does not go to the extreme of a Tertullian, a Kierkegaard, or a Shestov and condemn reason wholesale.

The attitude of the philosopher who is open to the claims of Revelation is different. He feels duty-bound by his intellectual conscience to examine the epistemic credentials of Biblical revelation lest he unjustifiably accept what he has no right to accept. This attitude is personified by Edmund Husserl. On his death bed, attended by nuns, open to the Catholic faith, he was yet unable to make the leap, remarking that it was too late for him, that he would need for each dogma five years of investigation.

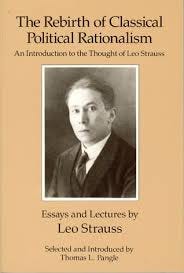

There is a tension here and it is the tension between Athens (Greek philosophy) and Jerusalem (the Bible), the two main roots of the West whose fruitful entanglement is the source of the West's vitality. As Leo Strauss sees it, it is a struggle over the unum necessarium, the one thing needful or necessary:

To put it very very simply and therefore somewhat crudely, the one thing needful according to Greek philosophy is the life of autonomous understanding. The one thing needful as spoken by the Bible is the life of obedient love. The harmonizations and synthesizations are possible because Greek philosophy can use obedient love in a subservient function, and the Bible can use philosophy as a handmaid; but what is so used in each case rebels against such use, and therefore the conflict is really a radical one. ("Progress or Return?" in The Rebirth of Classical Political Rationalism, University of Chicago Press, 1989, p. 246, bolding added.)

So is the Christian the true philosopher? Only in the sense that philosophy points beyond itself to something that is no longer philosophy but that completes philosophy while cancelling it. I am tempted to reach for an Hegelian trope while turning it on its head: if Christianity is true, then philosophy is aufgehoben, sublated, in it. If Christianity is true, then the Christian arrives at the truth that the philosopher at best aims at but cannot arrive at by his method and way of life, the life of autonomous understanding. To achieve what he aims at, the philosopher would have to be "as a little child" and accept in obedient love the gift of Revelation. But it is precisely that which he cannot do if he is to remain a philosopher in the strict sense, one who lives the life of autonomous understanding.

This is tension some of us live. The life of autonomous understanding and critical examination versus the life of child-like trust and obedient love.

The problem in what is perhaps its sharpest form is presented in the story of Abraham and Isaac.

The Christian life is not the philosophical life. It lies beyond the philosophical life and, if true, is superior to it.

But is Chrsitianity true?

We can and must ask this question. But reason cannot answer it. In the end, you have to decide what you will believe and how you will live.