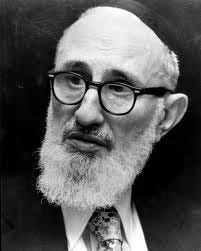

Soloveitchik on Proving the Existence of God

Joseph B. Soloveitchik's The Lonely Man of Faith (Doubleday 2006) is rich and stimulating and packed with insights. But there is a long footnote on p. 49 with which I heartily disagree. Here is part of it:

The trouble with all rational demonstrations of the existence of God, with which the history of philosophy abounds, consists in their being exactly what they were meant to be by those who formulated them: abstract logical demonstrations divorced from the living primal experiences in which these demonstrations are rooted. For instance, the cosmic experience was transformed into a cosmological proof, the ontic experience into an ontological proof, et cetera. Instead of stating that the the most elementary existential awareness as a subjective 'I exist' and an objective 'the world around me exists' awareness is unsustainable as long as the the ultimate reality of God is not part of this experience, the theologians engaged in formal postulating and deducing in an experiential vacuum. Because of this they exposed themselves to Hume's and Kant's biting criticism that logical categories are applicable only within the limits of the human scientific experience.

Does the loving bride in the embrace of her beloved ask for proof that he is alive and real? Must the prayerful soul clinging in passionate love ecstasy to her Beloved demonstrate that He exists? So asked Soren Kierkegaard sarcastically when told that Anselm of Canterbury, the father of the very abstract and complex ontological proof, spent many days in prayer and supplication that he be presented with rational evidence of the existence of God.

A man like me has one foot in Jerusalem and the other in Athens. Soloveitchik and Kierkegaard, however, have both feet in Jerusalem. They just can't understand what drives the philosopher to seek a rational demonstration of the existence of God. Soloveitchik's analogy betrays him as a two-footed Hierosolymian. Obviously, the bride in the embrace of the beloved needs no proof of his reality. The bride's experience of the beloved is ongoing and coherent and repeatable ad libitum. If she leaves him for a while, she can come back and be assured that he is the same as the person she left. She can taste his kisses and enjoy his scent while seeing him and touching him and hearing him. He remains self-same as a unity in and through the manifold of sensory modes whereby he is presented to her. And in any given mode, he is a unity across a manifold. Shifting her position, she can see him from different angles with the visual noemata cohering in such a way as to present a self-same individual. What's more, her intercourse with his body fits coherently with her intercourse with his mind as mediated by his voice and gestures.

I could go on, but the point is plain. There is simply no room for any practical doubt as to the beloved's reality given the forceful, coherent, vivacious, and obtrusive character of the bride's experience of him. She is compelled to accept his reality. There is no room here for any doxastic voluntarism. The will does not play a role in her believing that he is real. There is no need for decision or faith or a leap of faith in her acceptance of his reality.

Our experience of God is very different. It comes by fleeting glimpses and gleanings and intimations. The sensus divinitatis is weak and experienced only by some. The bite of conscience is not unambiguously of higher origin than Freudian superego and social suggestion. Mystical experiences are few and far-between. Though unquestionable as to their occurrence, they are questionable as to their veridicality because of their fitful and fragmentary character. They are not validated in the ongoing way of ordinary sense perception. They don't integrate well with ordinary perceptual experiences. And so the truth of these mystical and religious experiences can and perhaps should be doubted. It is this fact that motivates philosophers to seek independent confirmation of the reality of the object of these experiences by the arguments that Soloveitchik and Co. dismiss.

The claim above that the awareness expressed by 'I exist' is unsustainable unless the awareness of God is part of the experience is simply false. That I exist is certain to me. But it is far from certain what the I is in its inner nature and what existence is and whether the I requires God as its ultimate support. The cogito is not an experience of God even if God exists and no cogito is possible without him. The same goes for the existence of the world. The existence of God is not co-given with the existence of the world. It is plain to the bride's senses that the beloved is real. It is not plain to our senses that nature is God's nature, that the cosmos is a divine artifact. That is why one cannot rely solely on the cosmic experience of nature as of a divine artifact, but must proceed cosmologically by inference from what is evident to what is non-evident.

Soloveitchik is making the same kind of move that St. Paul makes in Romans 1: 18-20. Here is my critique of that move:

Is Atheism Intellectually Respectable?

Joe Carter over at First Things argues that "We have to abandon the politically correct notion that atheism is intellectually respectable." My view is that theism and atheism are both intellectually respectable. Carter makes his case by invoking St. Paul: