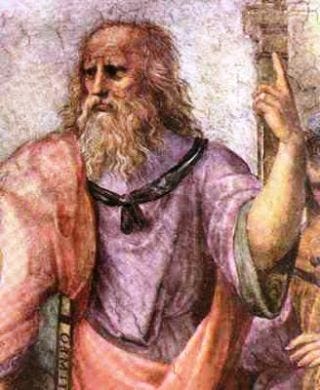

To understand Simone Weil, one must understand her beloved master, Plato. So let's interpret a passage from the Phaedo dialogue, and then compare it to some statements of Weil.

At Stephanus 83a we read, "...the perceptions of the eye, and the ear, and the senses are full of deceit." (tr. F. J. Church) The point is not that the senses are sometimes non-veridical, but that they tie us to a world that is not ultimately real, and that distracts us from the one that is. From the context it is clear that the point is not epistemological but axiological and ontological. It is not that the senses are unreliable, whether episodically or globally, in respect of the information they provide us about an external world of spatiotemporal particulars. They are reliable enough in providing us such information. The point is rather that the senses deceive us into conferring high value on what is of low value, and into taking as ultimately real what is derivatively real. For Plato the sense world is not unreal, but it is not fully real either.

It would be a mistake, therefore, to read the passage as an anticipation of the modern problematic of the external world from Descartes to Kant to G. E. Moore and beyond. The problem is not how we can come to have knowledge of an external world given that what is immediately given are only our ideas and representations, ideas and representations the contents of which would be the same whether or not there is an external world. The point is much deeper. The Platonic inquiry calls into question, not human knowledge of a physical world taken to be ultimately real, but the reality and importance of the physical world itself as correlate of the outer senses.

On the same page of the dialogue, we read that ". . . nothing which is subject to change has any truth." 'Truth' is here used ontically as equivalent to 'being' or 'real existence.' The mutable is not ultimately 'true' or ultimately real. Why not? Because it is subject to change. The idea is not that the mutable is a mere illusion, but that it lacks plenary reality, and that lacking full reality it lacks plenary value. I should add that what lacks plenary reality and value cannot play for us a soteriological role.

There are thus four ancient themes here, each of which is contested by the moderns qua moderns and the contemporaries qua contemporaries. (1) There is the idea that impermanence argues relative unreality. (2) There is the closely-related levels-of-reality theme which is hotly opposed in contemporary analytic philosophy, especially Down Under by John Anderson and his students, and here in the states by the formidable Peter van Inwagen and plenty of others. (3) There is the theme of the intertwinement of reality and value which finds expression much later in the history of thought in the scholastic slogan ens et bonum convertuntur (being and good are convertible) which I take to mean that what is (ens) is good just in virtue of its Being (esse) and in the measure that it possesses Being (esse), and that what is good is good in virtue of its Being (esse) and in the measure that it possesses Being (esse). Thus things in themselves are not axiologically neutral such that their value predicates are subjectively imposed; it is rather the case that things in themselves in their mind-independent reality are good because they are and in the measure that they are. (4) Finally, there is the theme that our salvation is bound up with our knowledge of what is ultimate real and thus ultimately good. This knowledge has ultimate truth and it is this truth that sets us free.

One who can sympathize with these four themes has Platonic intuitions. It may well be that any arguments one develops in support of these four theses will be no more than articulations of these deep intuitions or spiritual insights which one either has or does not have, depending, to allude to Fichte's famous saying, on what kind of person one is. (. . .was für eine Philosophie man wähle, hängt ... davon ab, was man für ein Mensch ist.) "What sort of philosophy one chooses depends on the sort of human being one is." (Thus a spiritually superficial fellow like Rudolf Carnap or David Stove is, predictably, a miserable positivist.)

A little farther down, around the middle of St. 83, we read, ". . . when the soul of any man feels vehement pleasure or pain, she is forced at the same time to think that the object, whatever it be, of these sensations is the most distinct and the truest, when it is not." Plato's point, again, is not that the senses deceive us about what is really there in the sense world, but that the senses deceive us into thinking that the sense world is a world of true being or ultimate reality. The point is perfectly plain in the light of the allegory of the cave in the Republic.

To find reality the soul must "gather herself together" and "stand aloof from the senses" using them "only when she must . . . ." Pleasure and pain, desire and fear (aversion) must be avoided since they pin the soul to the body, and by pinning it to the body, pin it to the changeful world of sense. Inner purification and meditation, by which the soul "gathers herself together," are necessary for the philosopher's approach to the Real. The true philosopher aims at a separation of the soul from the body, and so must not fear death. We fear death because we love the body and its pleasures.

We now turn to some statements by Weil. The following three paragraphs stand under the heading Profession of Faith which begins her Draft for a Statement of Human Obligations:

There is a reality outside the world, that is to say, outside space and time, outside man's mental universe, outside any sphere whatsoever that is accessible to human faculties.

Corresponding to this reality, at the centre of the human heart, is the longing for an absolute good, a longing which is always there and is never appeased by any object in this world.

Another terrestrial manifestation of this reality lies in the absurd and insoluble contradictions which are always the terminus of human thought when it moves exclusively in this world.

The first statement conveys the Platonic conviction that ultimate reality is beyond the world of sense. But Weil goes beyond Plato and deeper into mysticism by holding that the reality beyond the sense world is inaccessible to human faculties. At St. 84, Plato has Socrates say that (intuitive) reason is the faculty whereby we contemplate what is "true and divine and real."

The second statement conveys the Platonic thought that the soul's longing can never satisfied by any sense object.

The third statement suggests a way of arguing that the sense world cannot be ultimate: if we take it to be such we land among insoluble aporiai.