Philosophy from the Twilight Zone "The Lonely"

AI and advanced robotics make the questions raised by Rod Serling in 1959 pressing indeed, among them: Are robots persons? Do they have legal or moral rights?

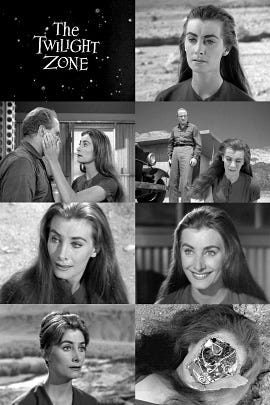

Rod Serling's Twilight Zone was an outstanding TV series that ran from 1959 to 1964. The episode "The Lonely" aired in November, 1959. I have seen it several times, thanks to the semi-annual Sy Fy channel TZ marathons. One can extract quite a bit of philosophical juice from "The Lonely" as from most of the other TZ episodes. I'll begin with a synopsis.

Synopsis

James A. Corry is serving a 50-year term of solitary confinement on an asteroid nine million miles from earth. Supplies are flown in every three months. Captain Allenby, unlike the other two of the supply ship's crew members, feels pity for Corry, and on one of his supply runs brings him a female robot named 'Alicia' to alleviate his terrible loneliness. The robot is to all outer appearances a human female. At first, Corry rejects her as a mere robot, a machine, and thus "a lie." He feels he is being mocked. "Why didn't they build you to look like a machine?" But gradually Corry comes to ascribe personhood to Alicia. His loneliness vanishes. They play chess with a set he has constructed out of nuts and bolts. She takes delight in a Knight move, and Corry shares her delight. They beam at each other.

But then one day the supply ship returns with news that Corry's sentence has been commuted as part of a general abolition of punishment by banishment to asteroids. Allenby informs Corry that there is room on the ship for only him and 15 lbs. of his personal effects. Alicia must be left behind. Corry is deeply distressed. "I'm not lonely any more. She's a woman!" Allenby replies, "She's a robot!" Finally, after some arguing back and forth, Allenby draws his sidearm and shoots Alicia in the face revealing her electronic innards. Corry's illusion of Alicia's personhood — if it is an illusion — dissipates and regretfully he boards the ship. The thirty minute episode ends with Serling's powerful closing narration:

On a microscopic piece of sand that floats through space is a fragment of a man's life. Left to rust is the place he lived in and the machines he used. Without use, they will disintegrate from the wind and the sand and the years that act upon them; all of Mr. Corry's machines — including the one made in his image, kept alive by love, but now obsolete — in the Twilight Zone.

Philosophical Analysis

The episode raises a number of philosophical questions. Here are just some of them.

Q1: Does personhood depend on what something is made of?

Corry is aware that Alicia, 'out of the box,' is a robot, a human artifact, and this knowledge inclines him to regard her at first as incapable of instantiating those attributes we associate with personhood as we experience them in the first-person way: sentience, the ability to feel and express emotions, the ability to reason, to make plans, and others. His thought is: She can't be a person because she is not made of flesh and blood.

But why should personhood require any particular material constitution? Why couldn't personhood be realized in different sorts of stuff? Not just any kind of stuff, of course, but sufficiently well-organized stuff. (You can't make a valve-lifter out of sawdust and spit, or a Phoenix monument out of ice, but the valve-lifter function is realizable in a variety of different materials with the right sorts of metallurgical properties.) In human beings such as Corry personhood is realized in a biologically human material substratum. But what is to stop personhood from being realized in some other sort of substratum, perhaps even a non-living substratum? Is being biologically alive a necessary condition of personhood? John Searle is one of the philosophers who would answer in the affirmative, but other philosophers of mind would demur.

When Allenby shoots Alicia in the head, revealing the electronic gadgetry inside, Corry's sense that Alicia is or was a person dissipates. But if someone had blown open a hole in Corry's skull, revealing brain matter, no one would take that as proof that Corry was not a person. “Look, he’s just a meathead! Where is the freedom and dignity and the right to life?”

Why is only one kind of material constitution, human brain matter, capable of supporting consciousness, self-consciousness, and the rest of the attributes of personhood? Is personhood perhaps a functional notion realizable in different types of material? The valve-lifter function above mentioned is multiply realizable. A simpler example is a kitchen spoon. The spoon function is realizable in plastic, wood, and several types of metal, but not in bread or ice. So if consciousness is realized in the wetware of Corry’s brain, why couldn’t it be realized in the hardware of Alicia’s intracranial computer? This question looms large in current discussions and is ably set forth in layman’s terms by Richard Susskind in How To Think About AI (Oxford UP, 2025) in Chapter 10, “Conscious Machines?”

Q2: If a person can be built, does this show that a person is purely material, or does the mind-body problem exist in this case as well?

Suppose that by the assembly of the right kind of material parts, one constructs a non-biologically-human but nonetheless full-fledged person. I don't mean what philosophers call a zombie, but a full-fledged person such as Alicia is portrayed as being in the TZ episode we are discussing. Thus the supposition is that this robotic person does in reality feel sensations and experience emotions just like we do. The question is not how we could know this to be the case. It is not the epistemological question about Other Minds. Q2 is an ontological question. The question is this. If we could build a person with a full-fledged inner life just like ours would this solve the mind-body problem by showing that a person is just a complex material system? Or would the mind-body problem arise in the robotic case just as it arises in our case? I think it would.

The robotic person has a mind and a body. It is not a zombie. It is really (in reality) the subject of object-directed and qualitative mental states. How then does the mere fact that the robotic person was constructed from material parts, indeed biologically inanimate material parts, show that she is purely material? Dualism, and perhaps even substance dualism, seems compatible with being constructed from material parts. Or does a person's having a material origin show that dualism is false? this strikes me as a genuine question.

Let me explain this a bit further. Suppose consciousness emerged in our evolutionary ancestors when their brains attained a certain level of neuronal complexity. Note that if x emerges from y, then x is not identical to y. Now ‘emergence’ naturally suggests emergence-from, in this case emergence from human brain matter. But given that (i) we do not understand the mechanism of this emergence, and given that (ii) the word ‘emergence’ by itself explains nothing but merely labels that which is to be explained, and thus merely ‘papers over’ the process of emerging, it might have been that the emergence of consciousness in our ancestors was not emergence-from, but emergence-on-the-occasion-of a certain level of neuronal and electro-chemical complexity. If so, consciousness and mentality in general emerge or ‘come on the scene’ both phylogenetically and ontogenetically not from below (from matter) but from above (from mind).

A Platonic way to cash this out would be in terms of pre-existent immaterial souls which enter animal brains/bodies when the brains have reached the requisite neuronal complexity. To give it a theistic twist, God implants pre-existent immaterial souls into animal organisms that either actually or potentially possess brains of the requisite complexity. Now on Christianity, there are no pre-existent individual souls. So a Christian theist could say that God creates ex nihilo immaterial souls on the occasion of human gametes coming together (sperm cell fertilizing egg cell) thus giving rise to a conceptus that in potency at least is of the requisite complexity to to support consciousness and mentality generally.

If I am right, then Corry committed a non sequitur. Allenby blew open Alicia’s head, revealing electronic innards. Corry wrongly inferred that she never was a person with an inner life, but always only a robot. Suppose Corry had grabbed Allenby’s gun and blown open his head revealing brain matter. Would Corry have concluded that Allenby was never a person with an inner life? No.

Q3. Is mentality or personhood a matter of ascription? A matter of the taking up of Dennett's "intentional stance?"

As Corry interacts with Alicia, he gradually comes to accept her as a person and a friend. After pushing her away in one scene, he interprets her verbal report, "You hurt me," and her tears as behavioral evidence of personhood. Could it be maintained that personhood is not a matter of some 'inner' reality, but a matter of ascription from the point of view of one who takes up the "intentional stance" with respect to an object of interpretation? Could one say that Alicia is a person, but that her personhood is not intrinsic to her but ascribed from without? Could one say that Alicia is a person, but only in relation to Corry who takes up the intentional stance toward the body in his visual field? But then you would have to say the same thing about Corry. You would have to say that Corry is not intrinsically a person, but is only a person in relation to Alicia who ascribes personhood to him. Is it coherent to think of Alicia and Corry alone on their asteroid ascribing personhood to each other, thereby constituting each other as persons? Ascription is object-directed, and thus an instance of intentionality. Dennett’s ascriptivist as opposed to realist theory of intentionality however, is untenable, as I argue elsewhere.

Q4. Is personhood and the uniqueness essential to personhood engendered by love?

Alicia was made in man's image, and "kept alive by love" as Serling intones in his closing comment. Alicia's value to Corry has something to do with his perception of her as unique, as a Thou to his I, as an irreplaceable individual, and not merely as an interchangeable instance of properties. Personhood seems to include such notions as irreducible individuality, haecceity, ipseity, interiority. These are not empirical attributes. How are they given? How constituted? Are they engendered by love? The great American philosopher Josiah Royce, now neglected, had penetrating things to say on this topic. Do we first become persons in a loving I-Thou relation? But this is a topic deep and wide; too deep and wide for a mere Substack article. See my Royce Revisited: Individuality and Immortality.