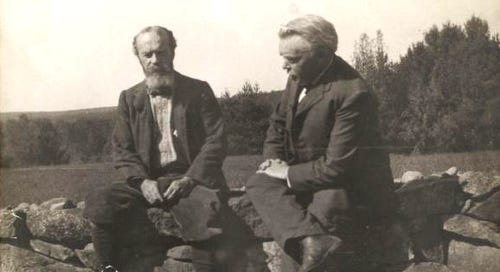

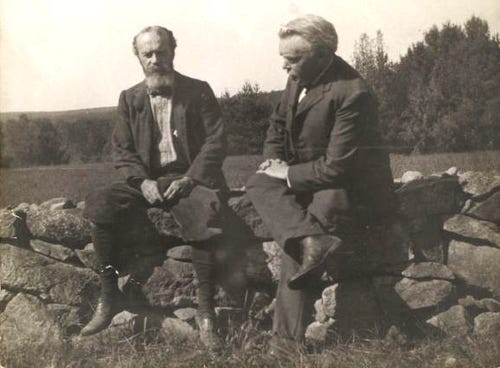

There are tough questions about the possibility and the actuality of divine revelation. An examination of some ideas of the neglected philosopher Josiah Royce (1855-1916) from the Golden Age of American philosophy will help us clarify some of the issues and problems. One such problem is this: How can one know in a given case that a putative piece of divine revelation is genuine? Before advancing to this question we need a few sections of stage-setting. (That's Royce on the right, by the way, and William James on the left. Surely it was degeneration when American philosophy came to be dominated by the likes of Willard Van Orman Quine and Richard Rorty.)

1. Concern for Salvation as Essential to Religion. It is very difficult to define religion, in the sense of setting forth necessary and sufficient conditions for the correct application of the term, but I agree with Royce's view that an essential characteristic of anything worth calling religion is a concern for the salvation of man. (The Sources of Religious Insight, Charles Scribner and Sons, 1912, p. 8) Religious objects are those that help show the way to salvation. The central postulate of religion is that "man needs to be saved." (8-9) Saved from what? ". . . from some vast and universal burden, of imperfection, of unreasonableness, of evil, of misery, of fate, of unworthiness, or of sin." (8) Religiously viewed, our state is wretched. Wretched are not merely the sick, the unloved, and the destitute; all of us are, even those of us who count as well off. The religiously sensitive are aware of our condition, the rest hide it from themselves by losing themselves in Pascalian divertissement. We are as if fallen from a higher state, our true and rightful state, into a lower one, and the sense of wretchedness is an indicator of our having fallen. We are in a dire state from which we need salvation but are incapable of saving ourselves by our own efforts, whether individual or collective.

2. The Need for Salvation. "Man is an infinitely needy creature." (11) But the need for salvation, for those who feel it, is paramount. The need depends on two simpler ideas:

a) There is a paramount end or aim of human life relative to which other aims are vain. (12)

b) Man as he now is, or naturally is, is in danger of missing his highest aim, his highest good. (12)

To hold that man needs salvation is to hold both of (a) and (b). I would put it like this. The religious person perceives our present life, or our natural life, as radically deficient, deficient from the root (radix) up, as fundamentally unsatisfactory; he senses or glimpses from time to time the possibility of a Higher Life; he feels himself in danger of missing out on this Higher Life of true happiness. If this doesn't strike a chord in you, then I suggest you do not have a religious disposition. Some people don't, and it cannot be helped. One cannot discuss religion with them, for it cannot be real to the them.

3. Religious Insight. Royce defines religious insight as ". . . insight into the need and into the way of salvation." (17) No one can take religion seriously who has not felt the need for salvation. But we need religious insight to show that we really need it, and to show the way to it.

4. Royce's Question. He asks: What are the sources of religious insight? Of insight into the need and into the way of salvation? Many will point to divine revelation through a scripture or through a church as the principal source of religious insight. But at this juncture Royce discerns a paradox that he calls the religious paradox, or the paradox of revelation.

5. The Paradox of Revelation. Suppose someone claims to have received a divine communication regarding the divine will, the divine plan, the need for salvation, the way to salvation, or any related matter. This person can be asked, "By what marks do you personally distinguish a divine revelation from any other sort of report?" (22-23) How is a putative revelation authenticated? By what marks or criteria do we recognize it as genuine? The identifying marks must be in the believer's mind prior to his acceptance of the revelation as valid. For it is by testing the putative revelation against these marks that the believer determines that it is genuine. One needs "a prior acquaintance with the nature and marks and, so to speak, signature of the divine will." (p. 25) But how can a creature who needs saving lay claim to this prior acquaintance with the marks of genuine revelation?

The paradox in a nutshell is that it seems that only revelation could provide one with what one needs to be able to authenticate a report as revelation:

Faith, and the passive and mysterious intuitions of the devout, seem to depend on first admitting that we are naturally blind and helpless and ignorant, and worthless to know, of ourselves, any saving truth; and upon nevertheless insisting that we are quite capable of one very lofty type of knowledge -- that we are capable, namely, of knowing God's voice when we hear it, of distinguishing a divine revelation from all other reports, of being sure, despite all our worthless ignorance, that the divine higher life which seems to speak to us in our moments of intuition is what it declares itself to be. If, then, there is a pride of intellect, does there not seem to be an equal pride of faith, an equal pretentiousness involved in undertaking to judge that certain of our least articulate intuitions are infallible?

Surely here is a genuine problem, and it is a problem for the reason. (103)

Is it a genuine problem or not? Can the church's teaching authority be invoked to solve the problem? Suppose a point of doctrine regarding salvation and the means thereto is being articulated at a church council. The fathers in attendance debate among themselves, arrive at a result, and claim that it is inspired and certified by the Holy Spirit. By what marks do they authenticate a putative deliverance of the Holy Spirit as a genuine deliverance? How do they know that the Holy Spirit is inspiring them and not something else such as their own subconscious desire for a certain result? But this is exactly Royce's problem.