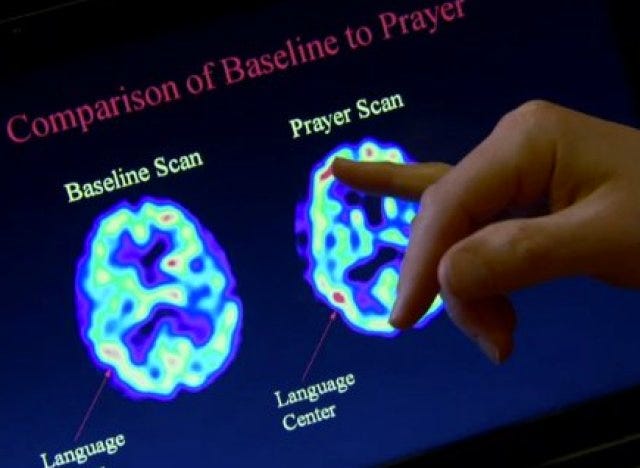

One aspect of contemporary scientism is the notion that great insights are to be gleaned from neuroscience about the mind and its operations. If you want my opinion, the pickin’s are slim indeed and confusions are rife. This is your brain on prayer:

A test subject is injected with a dye that allows the researcher to study brain activity while the subject is deep in prayer/meditation. The red in the language center and frontal lobe areas indicates greater brain activity when the subject is praying or meditating as compared to the baseline when he is not. But when atheists "contemplate God" — which presumably means when they think about the concept of God, a concept that they, as atheists, consider to be uninstantiated — "Dr. Newberg did not observe any of the brain activity in the frontal lobe that he observed in religious people."

The upshot?

Dr. Newberg concludes that all religions create neurological experiences, and while God is unimaginable for atheists, for religious people, God is as real as the physical world. "So it helps us to understand that at least when they [religious people] are describing it to us, they are really having this kind of experience. . . . This experience is at least neurologically real."

First of all, why do we need a complicated and expensive study to learn this? It is well-known that serious and sincere practitioners of religions will typically have various experiences as a result of prayer and meditation. (Of course most prayer and meditation time is 'dry' — but experiences eventually come.) The reality of these experiences as experiences cannot be doubted from the first-person point of view of the person who has them. There is no need to find a neural correlate in the brain to establish the reality of the experience qua experience. The experiences are real whether or not neural correlates can be isolated, and indeed whether or not there are any.

Suppose no difference in brain activity is found as between the religionists and the atheists when the former do their thing and the latter merely think about the God concept. (To call the latter "contemplating God" is an absurd misuse of terminology.) What would that show? Would it show that there is no difference between the religionists' experiences and the atheists'? Of course not. The difference is phenomenologically manifest, and, as I said, there is no need to establish the "neurological reality" of the experiences to show that they really occur.

Now I list some possible confusions into which one might fall when discussing a topic such as this.

Confusion #1: Conflating the phenomenological reality of a religious experience as experienced with its so-called "neurological reality." They are obviously different as I've already explained.

Confusion #2: Conflating the religious experience with its neural correlate, the process in the brain or CNS on which the experience causally depends. Epistemically, they cannot be the same since they are known in different ways. The experience qua experience is known with certainty from the first-person point of view. The neural correlate is not. One cannot experience, from the first-person point of view, one's own brain states as brain states. Ontically, they cannot be the same either, and this for two sorts of reasons. First, the qualitative features of the experiences cannot be denied, but they also cannot be identified with anything physical. This is the qualia problem. Second, religious/mystical experiences typically exhibit that of-ness or aboutness, that directedness-to-an-object, that philosophers call intentionality. No physical states have this property.

Confusion #3: Conflating a religious entity with its concept, e.g., confusing God with the concept of God. This is why it is slovenly and confused to speak of "contemplating God" when one is merely thinking about the concept of God. The journalist and/or the neuroscientist seem to be succumbing to this confusion.

Confusion #4: Conflating an experience (an episode or act of experiencing) with its intentional object. Suppose one feels the presence of God. Then the object is God. But God is not identical to the experience. For one thing, numerically different experiences can be of the same object. The object is distinct from the act, and the act from the object. The holds even if the intentional object does not exist. Suppose St. Theresa has an experience of — or an experience as of, to put the point with pedantic precision — the third person of the Trinity, but there is no such person. That doesn't affect the act-object structure of the experience. After all, the act does not lose its intentional directedness because the object does not exist.

Confusion #5: Conflating the question whether an experience 'takes an object' with the question whether the object exists.

Confusion #6: Conflating reality with reality-for. There is no harm is saying that God is real for theists, but not real for atheists if all one means is that theists believe that God is real while atheists do not. Now if one believes that p, it does not follow that p is true. Likewise, if God is real for a person it doesn't follow that God is real, period. One falls into confusion if one thinks that the reality of God for a person shows that God is real, period.

We find this confusion at the end of the video clip. "And if God only exists in our brains, that does not mean that God is not real. Our brains are where reality crystallizes for us."

This is knuckleheaded nonsense. First of all God cannot exist in our brains. Could the creator of the universe be inside my skull? Second, it would also be nonsense to say that the experience of God is in our brains for the reasons give in #2 above. Third, if "God exists only in our brains" means that the experience of God is phenomenologically real for those who have it, but that the intentional object of this experience does not exist, then it DOES mean that God is not real.

Confusion #7: Conflating the real with the imaginable. We are told that "God is unimaginable for atheists." But that is true of theists as well: God, as a purely spiritual being, can be conceived but not imagined. To say that God is not real is not to say that God is unimaginable, and to say that something (a flying horse, e.g.) is imaginable is not to say that it is real.

What I am objecting to is not neuroscience, which is a wonderful subject worth pursuing to the hilt. What I am objecting is scientism, in the present case neuroscientism, the silly notion that learning more and more about a hunk of meat is going to give us real insight into the mind and is operations and is going to solve the philosophical problems in the vicinity.

What did we learn from the article cited? Nothing. We don't need complicated empirical studies to know that religious experiences are real. What the article does is sow seeds of confusion. One of the confusions the article sows is that the question of the veridicality of religious experiences can be settled by showing their "neurological reality." Neither the phenomenological nor the neurological reality of the experience qua experience entails the reality of the object of the experience.

Genuine science cannot rest on conceptual foundations that are thoroughly confused.