Here, in The New York Review of Books:

To the Editors:

Thomas Nagel writes that “whether atheists or theists are right depends on facts about reality that neither of them can prove” [“A Philosopher Defends Religion,” Letters, NYR, November 8]. This is not quite right: it depends on what kind of theists we have to do with. We can, for example, know with certainty that the Christian God does not exist as standardly defined: a being who is omniscient, omnipotent, and wholly benevolent. The proof lies in the world, which is full of extraordinary suffering. If someone claims to have a sensus divinitatis that picks up a Christian God, they are deluded. It may be added that genuine belief in such a God, however rare, is profoundly immoral: it shows contempt for the reality of human suffering, or indeed any intense suffering.

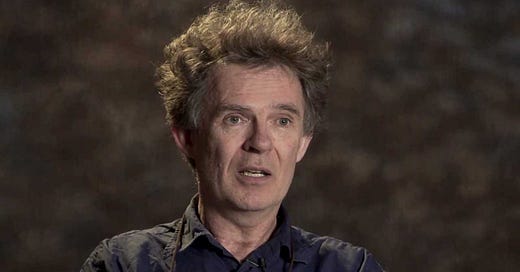

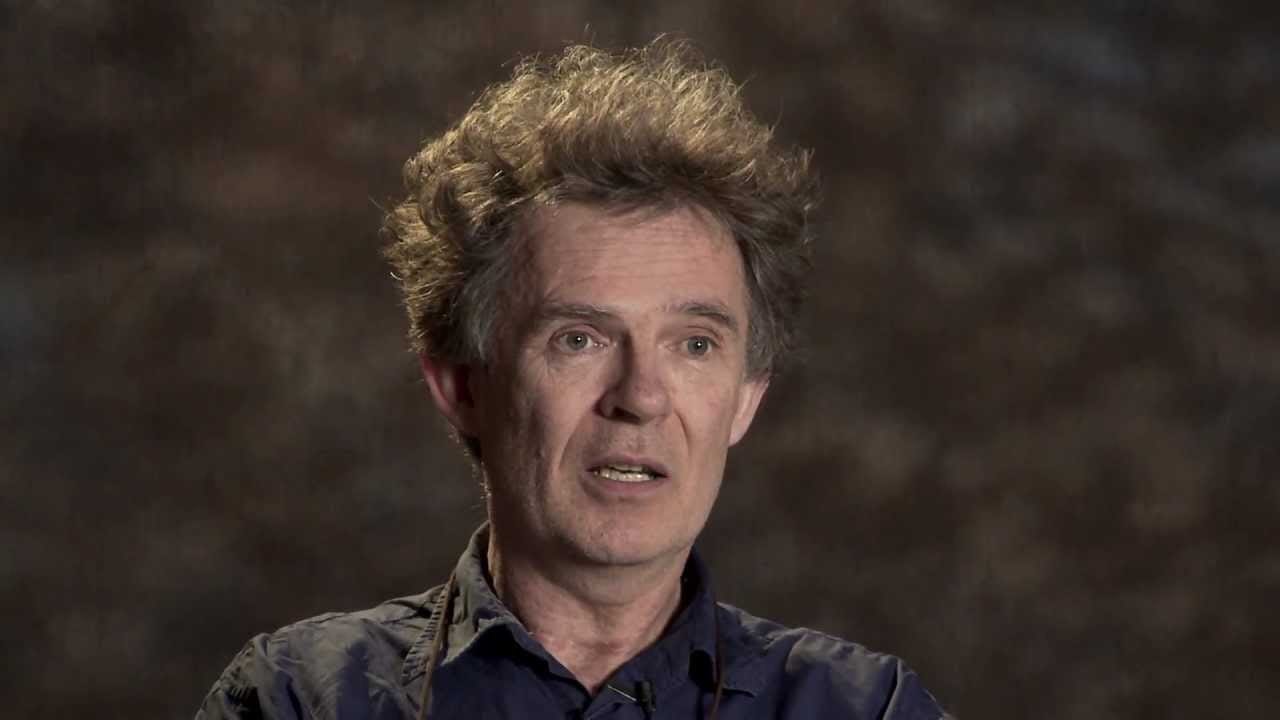

Galen Strawson

Strawson is telling us that it is certain that the God of Christianity does not exist because of the suffering in the world.

How is that for pure bluster?

What we know is true, and what we know with certainty we know without the possibility of mistake. When Strawson claims that it is certain that the Christian God does not exist, he is not offering an autobiographical comment: he is not telling us that it is subjectively certain, certain for him, that the Christian God does not exist. He is maintaining that it is objectively certain, certain in itself, and thus certain for anyone that the God of Christianity does not exist. From here on out 'certain' by itself is elliptical for 'objectively certain.'

And why is it certain that the Christian God does not exist? Because of the "extraordinary suffering" in the world. Strawson appears to be endorsing a version of the argument from evil that dates back to Epicurus and in modern times was endorsed by David Hume. The argument is often called 'logical' to distinguish it from 'evidential' arguments from evil. Since evidential or inductive or probabilistic arguments cannot render their conclusions objectively certain even if all of their premises are certain, Strawson must have the 'logical' argument in mind. Here is a version:

If God exists, then God is omnipotent, omniscient, and morally perfect.

If God is omnipotent, then God has the power to eliminate all evil.

If God is omniscient, then God knows when and where any evil exists or is about to exist.

If God is morally perfect, then God has the desire to eliminate or prevent all evil.

Evil exists.

If evil exists and God exists, then either God doesn’t have the power to eliminate or prevent all evil, or doesn’t know when or where evil exists, or doesn’t have the desire to eliminate or prevent all evil.

Therefore, God doesn’t exist.

It is a clever little argument, endlessly repeated, and valid in point of logical form. But are its premises objectively certain? This is not the question whether the argument is sound. It is sound if and only if all its premises are true. But a proposition can be true without being known to be true, and a fortiori, without being known to be true with certainty, i.e., with objective certainty. The question, then, is whether each premise in the above argument is objectively certain. If even one of the premises is not, then neither is the conclusion. I will now show that two of the premises are not objectively certain.

Consider (5). It it certain that evil exists? Is it even true? Are there any evils? No doubt there is suffering. But is suffering evil? I would say that it is, and I won't protest if you say that it is obvious that it is. But the obvious needn't be certain. It is certainly not the case that it is certain that suffering is evil, objectively evil. It could be like this. There are states of humans and other animals that these animals do not like and seek to avoid. They suffer in these states in a two-fold sense: they are passive with respect to them, and they find the qualitative nature of these states not to their liking, to put it in the form of an understatement. But it could be that these qualitatively awful states are axiologically neutral in that there are no objective values relative to which one could sensibly say something like, "It would have been objectively better has these animals not suffered a slow death."

The point I am making is that only if suffering is objectively evil could it tell against the objective existence of God. But suffering is objectively evil only if suffering is objectively a disvalue. So suffering is objectively evil and tells against the existence of God only if there are objective values and disvalues.

Perhaps all values and preferences are merely subjective along with all judgments about right and wrong. Perhaps all your axiological and moral judgments reduce to mere facts about what you like and dislike, what satisfies your desires and what does not. Perhaps there are no objective values and disvalues among the furniture of the world. I don't believe this myself. But do you have a rationally compelling argument that it isn't so? No you don't. So you are not certain that it isn't so.

And so you are not certain that evil exists. Evil ought not be and ought not be done, by definition. But it could be that there are no objective oughts and ought-nots, whether axiologically or agentially. There is just the physical world. This world includes animals with their different needs, desires, and preferences. There is suffering, but there is no evil. Since (5) is not certain, the conclusion (7) is not certain either.

Now consider (2): If God is omnipotent, then God has the power to eliminate or prevent all evil. Is that certain? Is it even true? Does God have the power to eliminate the evil that comes into the world through finite agents such as you and me? Arguably he does not. For if he did he would be violating our free will. By creating free agents, God limits his own power and allows evils that he cannot eliminate. Therefore, it is certainly not certain that (2) is true even if it is true. Reject the Free Will Defense if you like, but I will no trouble showing that the premises you invoke in your rejection are not certain.

Galen Strawson’s letter quoted above is pure ideologically-driven bluster from an otherwise brilliant and creative philosopher.