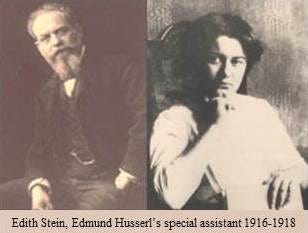

August 9th is the feast day of St. Theresa Benedicta of the Cross in the Catholic liturgy. She is better known to philosophers as Edith Stein (1891-1942), brilliant Jewish student of and assistant to Edmund Husserl, philosopher in her own right, Roman Catholic convert, Carmelite nun, victim of the Holocaust at Auschwitz, and saint of the Roman Catholic Church. One best honors a philosopher by re-enacting his thoughts, sympathetically but critically. Herewith, a bit of critical re-enactment.

In the 1920s Stein composed an imaginary dialogue between her two philosophical masters, Edmund Husserl and Thomas Aquinas. Part of what she has them discussing is the nature of faith.

One issue is whether faith gives us access to truth. Stein has Thomas say:

. . . faith is a way to truth. Indeed, in the first place it is a way to truths — plural — which would otherwise be closed to us, and in the second place it is the surest way to truth. For there is no greater certainty than that of faith . . . . (Edith Stein, Knowledge and Faith, tr. W. Redmond, ICS Publications, Washington, D. C., 2000, pp. 16-17)

Now comes an important question. What is it that we as philosophers want? We want the ultimate truths about the ultimate matters. If so, we should take these truths from whatever source offers them to us even if the source is not narrowly philosophical. We should not say: I will accept only those truths that can be certified by (natural) reason, but rather all truths whether certified by reason or 'certified' by faith. Thus Stein has Aquinas say:

If faith makes accessible truths unattainable by any other means, philosophy, for one thing, cannot forego them without renouncing its universal claim to truth. [. . .] One consequence, then, is a material dependence of philosophy on faith.

Then too, if faith affords the highest certainty attainable by the human mind, and if philosophy claims to bestow the highest certainty, then philosophy must make the certainty of faith its own. It does so first by absorbing the truths of faith, and further by using them as the final criterion by which to gauge all other truths. Hence, a second consequence is a formal dependence of philosophy on faith. (17-18)

But of course this cannot go unchallenged by Husserl. So Stein has him say:

. . . if faith is the final criterion of all other truth, what is the criterion of faith itself? What guarantees that the certainty of my faith is genuine? (20)

Or in terms of of the distinction between subjective (psychological) and objective (epistemic) certainty: what guarantees that the certainty of faith is objective and not merely subjective? The faiths of Jew, Christian, and Muslim are all different. How can the Christian be sure that the revelation he takes on faith has not been superseded by the revelation the Muslim takes on faith? And what about contradictory faith-contents? God cannot be both triune (as the normative Christian believes) and not triune (as the normative Muslim believes). So Christian and Muslim cannot both be objectively certain about their characteristic beliefs; at most they can be subjectively certain. For if you are objectively certain that such-and-such is the case, then such-and-such must be the case. Subjective certainty, on the other hand, has no epistemic value. (This paragraph is my gloss on the preceding quotation.)

Stein's Thomas replies to Husserl as follows:

Probably my best answer is that faith is its own guarantee. I could also say that God, who has given us the revelation, vouches for its truth. But this would only be the other side of the same coin. For if we took the two as separate facts, we would fall into a circulus vitiosus [vicious circle], since God is after all what we become certain about in faith.

[. . .]

All we can do is point out that for the believer such is the certainty of faith that it relativizes all other certainty, and that he can but give up any supposed knowledge which contradicts his faith. The unique certitude of faith is a gift of grace. It is up to the understanding and will to draw the practical consequences therefrom. Constructing a philosophy on faith belongs to the theoretical consequences. (20-22)

For Thomas and Stein, the certainty of faith is a gift of God. As such, it cannot be merely subjective. It is at once both subjective and objective, subjective as an inner certitude, objective as an effect of divine grace. Husserl, however, will ask how the claim that the certainty of faith is a divine gift can be validated. It is, after all, a contestable and contested claim. And not just by sophists and quibblers, but by sincere and brilliant truth seekers such as Husserl. How does one know that it is true? For Husserl, the claims that God exists and that the Christian revelation is divine revelation are but dogmatic presuppositions. They need validation because of the existence of competing claims such as those made by Jews and Muslims and atheists.

If, as Stein says, "faith is its own guarantee," then, since the faith of the Christian and the faith of the Muslim are contradictory with respect to certain key propositions, it follows that one of these faiths offers a false guarantee. You can see from this that the Thomas-Stein stance leaves something to be desired. But Husserl's approach has problems of its own. Closed up within the sphere of his subjectivity, man cannot reach the truly Transcendent, which must irrupt into this sphere and cannot be constituted (Husserl's term) within it. The truly Transcendent is not a transcendence-in-immanence. It cannot be a constituted transcendence.

If man is indeed a creature, there is something absurd about measly man hauling the Creator before the bench of finite reason there to be rudely interrogated about his credentials. On the other hand, the claim that man is a creature is not objectively self-evident but a claim like any other, and man must satisfy his intellectual conscience with respect to this claim. It is precisely his freedom, responsibility, and love of truth that drive him to ask: But is it true? And how do we know? And isn't it morally shabby to fool oneself and seek consolation in a fairy tale?

Paradoxically, God creates man in his image and likeness, and thus as free, responsible, and truth-loving; it is these characteristics that then motivate man to put God in the dock.

The Incompatibility of Husserl's Egocentrism and Thomas's Theocentrism

Let's give the last word to Stein's Aquinas:

The course that you have followed has led you to posit the subject as the start and center of philosophical inquiry; all else is subject-related. A world constructed by the acts of the subject remains forever a world for the subject. You could not succeed — and this was the constant objection that your own students raised against you — in winning back from the realm of immanence that objectivity from which you had after all set out and insuring which was the point. Once existence is redefined as self-identifying for a consciousness -- such was the outcome of the transcendental investigation -- the intellect will never be set at its ease in its search for truth. (31-32)

A brief comment in explanation of the last sentence. For Thomas and other realists, it is built into the very concept of existence that that which exists exists independently of consciousness. Thus if the tree in the garden exists, it exists whether or not it appears to any conscious being. On Husserl’s transcendental-phenomenological idealism, however, the existence of the tree is "redefined as self-identifying for a consciousness," which is to say that its existence is nothing other than the synthetic unity of the noemata in which it appears to the subject, a unity that derives from the unifying activities of transcendental consciousness. This is a thoroughly modern (and idealist) understanding of existence. Compare Panayot Butchvarov's theory of existence as the indefinite identifiability of what he calls objects and distinguishes from entities, and Hector-Neri Castañeda's theory of existence as "consubstantiation" of "ontological guises." (See my article, “Existence and Indefinite Identifiability,” Southwest Philosophy Review, vol.11, no. 2, July 1995, pp. 171-186.)

Now for the crux of the matter as Thomas replies to Husserl.

Moreover, this shift in meaning [of existence], especially by relativizing God himself, contradicts faith. (emphasis added) So here we may well have the sharpest contrast between transcendental phenomenology and my philosophy: mine has a theocentric and yours an egocentric orientation. (32)

So there you have it. There are two opposing conceptions of philosophy, one based on the autonomy of reason, and with it the exclusively internal validation of all knowledge claims, the other willing to sacrifice the autonomy of reason for the sake of truths which cannot be certified by reason or subjectively validated but which are provided by faith in revelation, a revelation that must simply be accepted in humility and obedience. It looks as if one must simply decide which of these two conceptions to adopt, and accept that the decision cannot be justified by (natural) reason.

My task, in this and in related posts, is first and foremost to set forth the problems as clearly as I can. Anyone who thinks this problem has an easy solution does not understand it. It is part of the tension between Athens and Jerusalem.