I have in mind Augustine's Confessions and Pascal's Pensées. If you read these books and they do not speak to you, if they do not move you, if they do not elicit a heart-felt Yes, then it is a good bet that you don't have a religious bone in your body. It is not a matter of intelligence but of sensibility.

"He didn't have a religious bone in his body." I recall that line from Stephanie Lewis' obituary for her husband David, perhaps the most brilliant American philosopher of the postwar period. He was highly intelligent and irreligious. Others are highly intelligent and religious. Among contemporary philosophers one could mention Alvin Plantinga, Peter van Inwagen, and Richard Swinburne. The belief that being intelligent rules out being religious casts doubt on the intelligence of those who hold it.

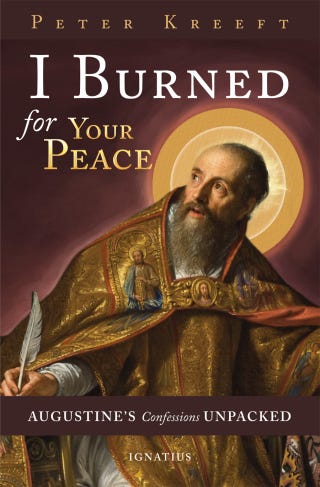

Let us suppose that you do not have the time or the stamina or the education to read Augustine's great book itself. Then I recommend to you on this, the feast day of St. Augustine, Peter Kreeft's I Burned for Your Peace: Augustine's Confessions Unpacked (Ignatius Press, 2016). It consists of key quotations with commentary by Kreeft.

But don't expect a high level of philosophical rigor. It is a work of popular apologetics by a master of that genre.

Kreeft's lack of philosophical rigor is illustrated by his view that "The refutation of this materialism is simple." (147)

For a long time Augustine struggled with the question of how there could be purely spiritual realities such as God and the soul. He was in the grip of a materialism according to which everything that is real must have a bodily nature and occupy space. But then he noticed that the mental acts by which we form bodily images are not themselves bodily images. My image of a cat, for example, has shape and color, but the mental act of imagining does not have shape and color. One can easily conjure up the image of a hard-travelin’ cat like Buddy below; one cannot. however, form a mental image of the imagining of such a cat.

As Kreeft puts it:

The imagination cannot imagine itself. The understanding, however, can understand itself. We can have a concept of the act of conceiving, and we can also have a concept of the act of imagining. [. . .] The light of the projection machine must transcend the images it projects on the machine. A material image cannot create an image; only an immaterial soul can.

It is exceedingly strange that many otherwise intelligent philosophers today simply cannot see this point when they embrace a materialist "solution" to the mind-body problem." (148)

Now I reject materialism about the mind, but surely this is an inconclusive argument. It fails in two ways. It fails to prove that mental acts are not states of the brain, and it also fails to prove that mental acts have their seat in an immortal soul.

I grant that there are mental acts. It is not obvious that there are, but I believe that there are in agreement with Edmund Husserl, and in defiance of such luminaries as Bertrand Russell. A mental act is an object-directed mental state, an intentional experience (ein intentionales Erlebnis) in Husserl’s terminology. What the act is of, the intentional object of the act, is no part of the act. So we distinguish act from object. in the Buddy case, the act of imagining a cat from the object imagined, the cat as imagined.

Now it must be granted to Kreeft that phenomenological reflection fails to note any physical or spatial features in the act of imagining or in any act of any type. When we reflect on our acts of awareness, whether they be imaginative, memorial, perceptual or whatever, we find no colors or shapes or sizes or material attributes. I can easily imagine a cat much bigger than Buddy, but I cannot imagine an act of imagining bigger than some other such act. And so when we introspect these operations of our minds we find no evidence that they are brain processes. On the phenomenological face of it, introspection is not the introspection of brain states.

To take an example from outer perception, if I see a coyote, I see something moving, or perhaps not moving, in space relative to other objects in space such as cacti and fence posts. Not so when I reflect upon my seeing of the coyote: I do not see axons and dendrites, the diffusion of sodium ions across synaptic junctions, etc. I don’t see anything spatial or physical. I don’t see a brain event or process. In fact, I don’t literally see anything in the sense of ‘see’ in which I see a coyote. And yet I am aware, not merely of a coyote, but of my seeing of a coyote, a reflective or introspective awareness expressible by the sentence, “I see a coyote.”

Absence of evidence, however, is not conclusive evidence of absence. The lack of evidence that mental acts are material does not prove that they are not material. It might be that mental acts are brain events, but that we are unable to cognize them in their true nature as brain events. It may be that our cognitive architecture is such as to disallow epistemic access to mental states as they are in reality by those who are experiencing them That they do not appear to be material does not prove or demonstrate that they are immaterial. What Kreeft is aiming at, however, is a ‘knock-down’ (rationally coercive) deductive argument, one that proves it conclusion and does not merely render it somewhat probable. He fails to satisfy that exacting demand.

The late Australian materialist David M. Armstrong defends materialism about the mind against arguments like the one sketched above by citing the Headless Woman Illusion (Sketch for a Systematic Metaphysics, Oxford 2010, pp. 106-107):

The illusion is brought about by exhibiting a woman (or, of course, a man!) against a totally black background with the head of the woman swathed with the same black material. It is apparently very striking, and could lead unsophisticated persons to think that the woman lacks a head. It is clear what is going on here. The spectators cannot see the head, and as a result make a transition to a strong impression that there was no head to see. An illegitimate operator shift is a work, taking people from not seeing the head to seeming to see that the woman did not have a head. The shift of the ‘not’, the operator, occurs because it is, in the circumstances, the natural and normally effective way to reason. If you can’t see anybody in the room, you may conclude, very reasonably, there is nobody in the room. In general, you will be right. In the same way, we emphatically do not perceive introspectively that the mind is [a] material process in our heads, so we have the impression that it is not material. This seems to nullify the force of the Argument from Introspection, while still explaining the seductiveness of the reasoning.

Armstrong’s point is that the Argument from Introspection is not rationally compelling. It does not refute materialism. Kreeft quite obviously thinks that it is, and that it does, which is why he thinks it “exceedingly strange that many otherwise intelligent philosophers today simply cannot see this point when they embrace a materialist "solution" to the mind-body problem." (148)

That's one problem with Kreeft’s view. A second is that he moves immediately from the immateriality of mental acts to an immaterial soul substance as subject of these acts. That move needs to be mediated by argument, argument he doesn’t supply. If a mental act were an action, one might argue that actions presuppose an agent who performs them; a mental act, however, is not an action. But this is a tale too long for the telling. Brevity is the soul of blog, and tomorrow’s another day.